Asthma ranks second among the most prevalent chronic respiratory diseases worldwide1, whereas up to 25% of adult-onset asthma is work-related. Work-related asthma (WRA) refers to asthma that is either caused by workplace exposures or preexisting/concurrent asthma worsened by workplace conditions2. Workers continuously exposed to WRA triggers are more likely to have uncontrolled asthma leading to significant morbidity, poorer quality of life and loss of productivity at work. Of note, asthma attack is one of the common symptoms of sick building syndrome (SBS)3. Thus the risk factors associated with the building where people working are noteworthy. Given the wide range of potential triggers of WRA, the joint efforts by employees, employers, and the government are crucial in addition to medical support in controlling the onset of WRA.

The Disease Burden of Asthma

Asthma is a common chronic lower respiratory disease characterised by recurrent attacks of breathlessness and wheezing, chest tightness and coughing4. Recent estimates suggested that the disease directly affects over 358 million individuals globally5. In Hong Kong, a previous territory-wide household survey reported that about 68,000 individuals suffered from asthma4. Given asthma can affect both adults and children, the disease is a major cause of loss in productivity and school absenteeism6. This highlights the indirect costs of the disease apart from its direct medical expenses.

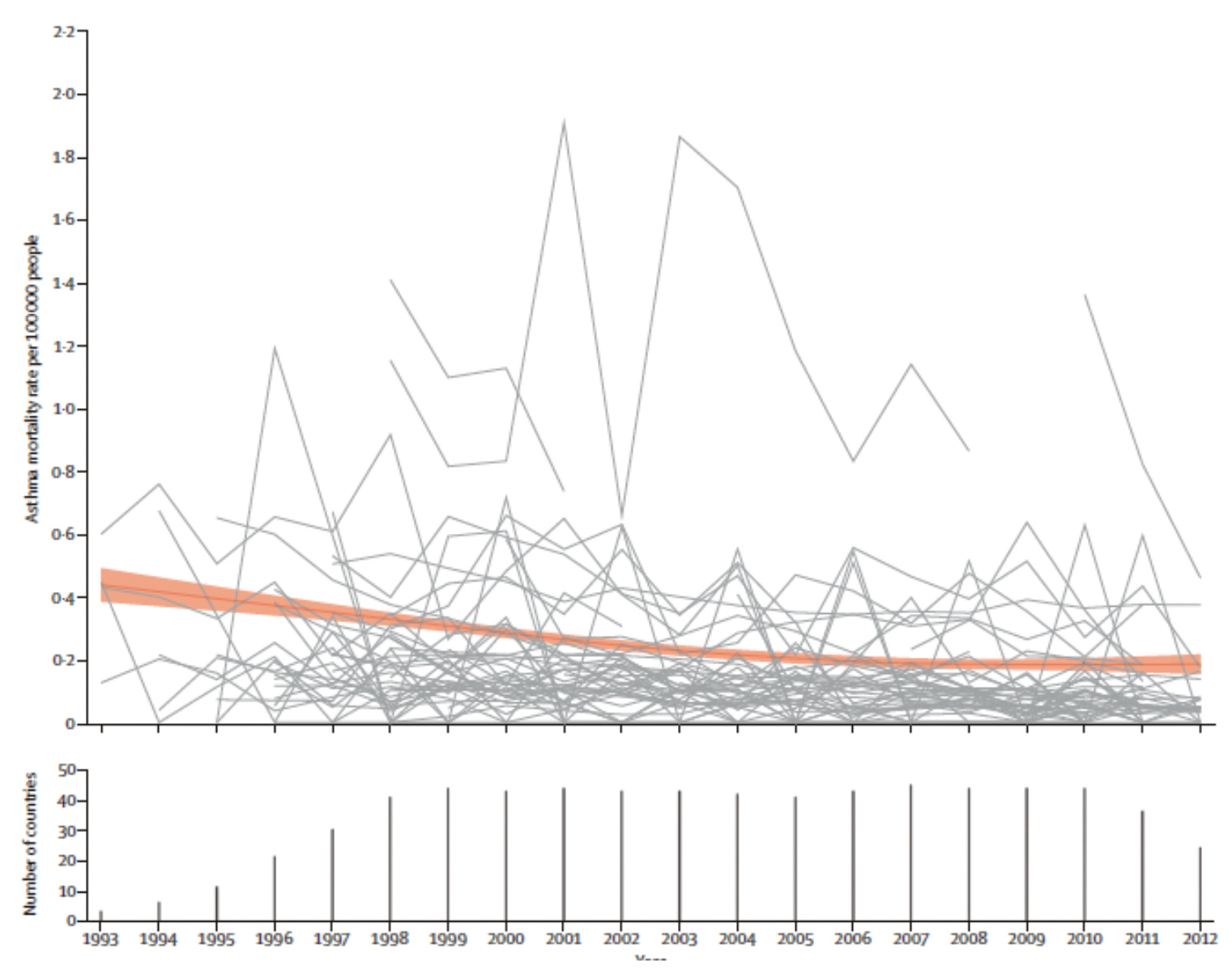

Despite advances in therapeutics for asthma, no significant reduction in global asthma mortality can be observed, which remains at 0.19 deaths per 100,000 people (Figure 1)7. Of importance, inadequate control of asthma continues to present a severe problem. According to the American Thoracic Society (ATS), refractory asthma encompasses several subgroups of patients with asthma that is severe, corticosteroid-dependent/resistant, difficult to control, brittle or irreversible8. Patients with inadequately controlled asthma often have limited therapeutic options and have a high risk of severe morbidity and mortality.

Despite advances in therapeutics for asthma, no significant reduction in global asthma mortality can be observed, which remains at 0.19 deaths per 100,000 people (Figure 1)7. Of importance, inadequate control of asthma continues to present a severe problem. According to the American Thoracic Society (ATS), refractory asthma encompasses several subgroups of patients with asthma that is severe, corticosteroid-dependent/resistant, difficult to control, brittle or irreversible8. Patients with inadequately controlled asthma often have limited therapeutic options and have a high risk of severe morbidity and mortality.

Figure 1. Age-standardised asthma mortality rates for the age group of 5-34 years in 46 countries for the years 1993–20127

Major Risk Factors of Asthma

The fundamental causes of asthma are yet to be fully understood. Nonetheless, many risk factors and triggers of the disease have been recognised. For instance, genetic factors have been shown to contribute to the development of asthma. A cohort study by Ullemar et al (2016) involving 25,306 Swedish twins aged 9 or 12 years demonstrated that the heritability of any childhood asthma was 0.829. Besides, obesity has been reported to increase the risk of late-onset asthma by approximately 50%, whereas obese asthmatics are likely to have worse asthma control and increased rates of healthcare utilisation due to asthma6. Moreover, a broad spectrum of indoor or outdoor allergens, such as house dust mites in bedding, carpets and stuffed furniture, pollens, etc., and air pollutants, including exhaust gas from cars and chemical irritants in the workplace, are common environmental triggers4.

Remarkably, it is well-documented that active or passive tobacco smoke exposure exacerbates asthma. A meta-analysis by Burke et al (2012) demonstrated that exposure to passive smoking increases the incidence of wheezing and asthma in children and young people by at least 20%10. More recently, Tiotiu et al (2021) showed that current smokers with asthma exhibited worse clinical and functional respiratory outcomes than never-smokers and former smokers, supporting the importance of smoking cessation11.

On the other hand, an accumulating body of evidence suggests a causal relationship between psychosocial stressors and asthma development as well as morbidity, whereas stress indicators included adverse life events, work-related stress, bereavement, etc. The general mechanistic paradigm of the effect of stress on the developing respiratory system is that stress disrupts immune, neuroendocrine, and autonomic function causing changes to normal lung growth and development12.

With a better understanding of asthma, more risk factors for the disease have been identified. Avoiding the risk factors and triggers might help prevent asthma or reduce its impact, hence improving patient outcomes.

Work-related Asthma - The Silent Risk at the Workplace

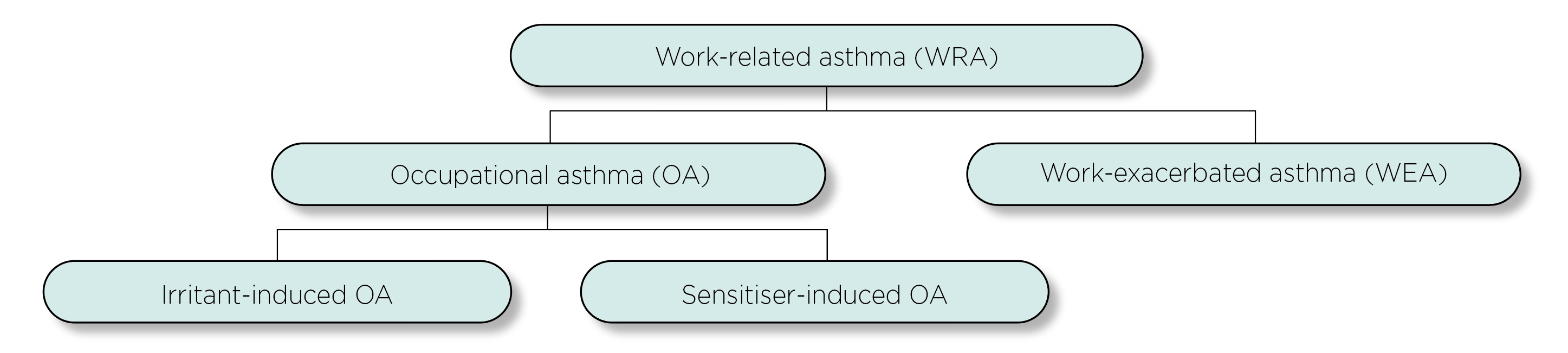

While most people spend a significant amount of time in their workplace every day, many risk factors and triggers of asthma are related to the working conditions and/or existing in the workplace. Notably, approximately 25% of adult-onset asthma was attributed to workplace exposure13. Work-related Asthma (WRA) is a general term including both asthma caused by an inciting exposure in the workplace, referred to as occupational asthma (OA), and asthma that is worsened by workplace conditions is known as work-exacerbated asthma (WEA). In particular, OA can be caused by sensitisers or irritants, while sensitiser-induced (allergic) condition is more common compared to irritant-induced (non-allergic) asthma

(Figure 2)1. WRA is a common cause of reduced quality of life, loss in productivity, increased utilisation of healthcare services, and unfavourable socioeconomic outcomes. Essentially, unrecognised and untreated WRA would potentially progress to severe asthma, refractory asthma, or both14.

It is crucial to realise that not only would workers in dusty or unsterile workplaces get WRA, but any working individual could suffer, including office workers and healthcare professionals working in sterilised environments. Many substances and conditions in the workplace can trigger asthma symptoms, such as cleaning products, dust mites, extreme temperatures, humidity, and even plants in the office. Of note, poor ventilation in the workplace can increase the amount of exposure to indoor pollutants and triggers. Besides, work-related emotional stress is also a potential trigger of asthmatic symptoms15. Notably, the duration of exposure is an essential factor determining the development of WRA13.

Figure 2. Relationship of asthma to the workplace

WRA and the Sick Building Syndrome

Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) consists of a group of mucosal, skin, and general symptoms that are temporally related to working in particular buildings. It is the workers who are symptomatic, but the building or its services are the cause3. Tiredness is the most common manifestation of SBS, which may start within a few hours after coming to work and improve in a few minutes after leaving the building. Besides, stuffy noses and dryness of the throat, which may lead to hoarseness of voice, are prevalent mucosal symptoms associated with SBS16. Moreover, gastrointestinal disturbance, sensitivity to odours, and neurotoxic effects (e.g. headache and irritability) are common among people who suffer from SBS as well17.

Remarkably, an increased incidence of asthma attacks, including chest tightness and wheezing, has been reported to be associated with SBS3. Of note, some of the factors responsible for SBS would also increase the risk of asthma. For instance, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which can be generated from adhesives, photocopiers, pesticides, and cleaning agents, are the most common contaminants of indoor air triggering SBS symptoms3. The compounds, especially aromatic compounds and aliphatic compounds, are also associated with exacerbated asthma symptoms18.

Besides, biological contaminants, including pollen, fungus, moulds, etc., can breed in stagnant water accumulated in humidifiers, drainpipes and ducts. Whereas air-conditioning systems can recirculate pathogens and spread them throughout the building. Many of these contaminants would probably increase the risk of asthma attacks4. Therefore, it is crucial to take workplace conditions into account in controlling WRA.

Joining Hands in Controlling WRA

If an individual has developed asthmatic symptoms or has the symptoms gotten worse (e.g. increased frequency of asthma rescue inhaler usage) after a new job or a change in the workplace, this hints at the onset of WRA. Suppose the symptoms are improved when away from work (e.g. on weekends or holidays), this further supports the diagnosis of WRA15. The management of WRA requires pharmacotherapy similar to that of non-WRA. However, it is essential to consider control of the causative workplace exposure since ongoing exposure will likely lead to declining lung function and worsening asthma control. Accordingly, in addition to the diagnosis of asthma, the onset or exacerbation of asthmatic symptoms after entering the worksite of interest, the potential associations between asthma symptoms and work, and the workplace exposure to agents known to cause asthma have to be considered in diagnosing WRA1.

While medical intervention is crucial in controlling asthmatic symptoms, employers and/or the management of the workplaces play a vital role in reducing the occurrence of risk factors and triggers of asthma in the related locations, which in turn minimises the risk of WRA. In particular, routine evaluation of indoor air quality (IAQ) and identification of the contaminants by air sampling is essential. Notably, the inspection of the sources of contamination, such as photocopiers, insulation and cleaning materials, is recommended. Additionally, measurement of temperature, humidity, air movement and other comfort parameters in the workplace should be included in the evaluation. Upon the routine evaluation, modification or removal of pollutant sources is needed3.

Apart from routine monitoring, proper design of the working environment can also reduce the risk of WRA. For instance, proper design and installation of heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems would improve ventilation rates and air distribution and facilitate the removal of air contaminants. On the other hand, paints, solvents, pesticides and adhesives should be stored in closed containers in well-ventilated areas3.

In Hong Kong, the Occupational Safety and Health Ordinance is established to ensure the safety and health of employees when they are at work and to improve the safety and health aspects of working environments of employees. Moreover, the Ordinance addresses the safety and health standards applicable to certain hazardous processes, plants and substances used or kept in workplaces19. While the Ordinance prescribes measures that will make workplaces safer and healthier for employees, employers have a legal obligation to make reasonable accommodations for their employees.

Besides workplace settings, reasonable arrangements in working conditions for improving the safety and health of employees are preferable. Remarkably, redeployment of jobs with the absence or reduction of exposure to triggers would help prevent WRA onset. It is vital to provide suitable protective clothing and masks for workers with unavoidable exposure to risk factors or triggers.

Notably, effective communication between employees and employers or the management of the workplace is essential in controlling WRA that frontline workers are encouraged to provide recommendations to eliminate or reduce triggers in the workplace, whereas the employers should provide education on WRA and the related risk factors for the employees to enhance the awareness on the disease.

WRA Is Never a Component of Your Work

Asthma is a common disease affecting millions of people globally and would significantly impact the quality of life of patients. Provided the evidence on the increased risk of asthma attacks upon exposure to the risk factors and triggers in various workplaces, most of the working population is inevitably exposed to the risk. Undoubtedly, medical professionals play a core role in the management of asthma. Nonetheless, effective control of WRA requires effort from a wide scope of stakeholders, including employees, employers, and the government. Moreover, further investigations to improve the characterisation of WRA can facilitate the identification of high-risk industries and occupations and hence establish the associated preventive measures.

References

1. Roio et al. J Bras Pneumol 2021; 47. DOI:10.36416/1806-3756/E20200577. 2. Mungan et al. Turkish Thorac J 2019; 20: 241–7. 3. Joshi. Indian J Occup Environ Med 2008; 12: 61–4. 4. Department of Health. Asthma Awareness. Non-Communicable Dis Watch 2017. 5. Gruffydd-Jones et al. J Asthma Allergy 2019; 12: 183. 6. Kuruvilla et al. Respir Med 2019; 149: 16–22. 7. Ebmeier et al. Lancet (London, England) 2017; 390: 935–45. 8. Peters et al. Respir Med 2006; 100: 1139–51. 9. Ullemar et al. Allergy 2016; 71: 230–8. 10. Burke et al. Pediatrics 2012; 129: 735–44. 11. Tiotiu et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 1–12. 12. Stern et al. Semin Immunopathol 2020; 42: 5–15. 13. Hoy et al. Respirology 2020; 25: 1183–92. 14. Friedman-Jimenez et al. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 36: 388–407. 15. Harber et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197: P1–2. 16. Burge. Occup Environ Med 2004; 61: 185. 17. Nag. Off Build 2019; : 53. 18. Paterson et al. Environ Res 2021; 202: 111631. 19. Cap. 509 Occupational Safety and Health Ordinance.