Specialist in Paediatric Immunology,

Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Recognition and Treatment of Patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is one of the most common form of chronic inflammatory arthritis in children and adolescents aged under 16 affecting their physical as well as psychological and social well-being. While a wide spectrum of therapeutics for JIA are emerging, long-term management of the disease is a challenging clinical issue. Notably, a portion of children with JIA have ongoing disease in adulthood associated with limitation in everyday life. To optimise the patients’ outcomes, early diagnosis and timely treatment are needed. Particularly, the role of a multidisciplinary team of professionals in the transition from paediatric to adult rheumatology care is crucial. In a recent interview, Dr. Patrick Chong Chun Yin, Specialist in Paediatric Immunology, Allergy and Infectious Diseases, highlighted the essentials in managing JIA and shared his opinions on controlling the risk of long-term impacts of the disease.

A Brief Glance at JIA

JIA is defined as a childhood chronic inflammatory arthritis with onset prior to age 16 years and a minimum duration of 6 weeks, following the exclusion of other causes. Currently, the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classifies JIA into 7 categories defined by the number of joints involved, presence or absence of extra-articular manifestations, and presence or absence of additional markers including rheumatoid factor (RF) and human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27)1.

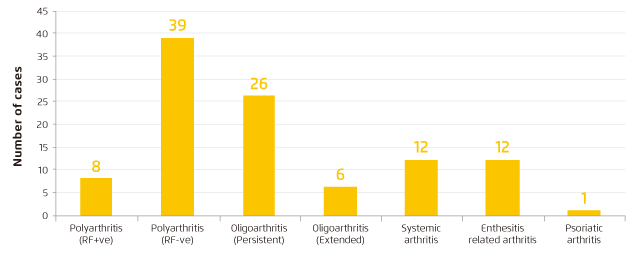

The true incidence and prevalence are difficult to be assessed clinically since nomenclature and disease criteria have changed over time2. Previous epidemiological study suggested that the estimated global incidence of JIA varied from 1.6 and 23 cases per 100,000 children3. A local inter-hospital surveillance study of JIA by Lee et al (2003) reported that the two most common subtypes were RF-negative polyarticular (37%) and persistent oligoarticular JIA (24%) respectively (Figure 1)4.

Figure 1. Local JIA course type distribution4

In view of common clinical manifestations of JIA, Dr. Chong stated that children with JIA commonly complained on the pain in joints of legs and/or arms and limping gaits. Of note, surrounding muscles of the joints may become atrophic as the children becomes more immobile2. Hence, it is important to examine the signs of inflammation of the joints in diagnosing JIA. “Solely joint pain may not indicate inflammation, but there are other possibilities for the pain in joints,” he mentioned. Inflammatory arthritis is characterised by the presence of pain, increase warmth, redness, swelling and limitation of movement. Moreover, the number of joints affected has to be taken into account. In some cases, the location of affected joints may not be easily observed, such as temporomandibular joints, hips and spine.

Although there are well-established definitions for JIA, systemic onset JIA (SoJIA) which manifests differently as compared to other subtypes. Patients may have persistent fever for 2 weeks or more and it is accompanied by evanescent erythematous rash during fever. That would occur in prior to the onset of arthritis. “Persistent fever in SoJIA patients may trigger haemophagocytosis which can be aggressive and fatal. Thus, upon the symptoms are observed, timely diagnosis and treatment are vital,” addressed Dr. Chong. In chronic arthritis with diagnosis and treatment in the latter course, irreversible damage of the joints may have been occurred. The damage would result in chronic pain and limited mobility. JIA can affect other organs such as the eyes. Moreover, uncontrolled inflammation would also affect the growth and development of children. Besides, the chronic pain would significantly impair the quality of life of the children, including their emotions and learning. With joint deformity and abnormal postures, children with JIA may be stigmatised by their peers resulting in adverse psychosocial impacts.

Diagnosis and Classification of JIA

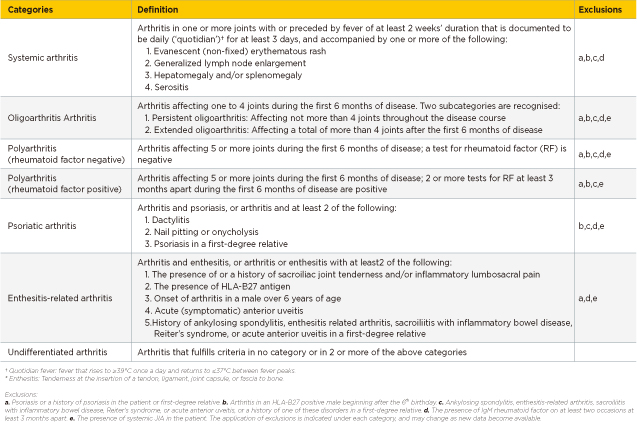

Clinical observation is the first step to evaluate the number and location of affected joints. The classification of JIA recommended by the ILAR is listed in Table 11. Dr. Chong emphasised that awareness of front-line physicians or family doctors on clinical symptoms of JIA such as the signs of arthritis, rash development (Figure 2)5 and persistent fever would facilitate early diagnosis and timely treatment.

Figure 2. (Left) An 18-month-old girl with arthritis in her right knee, and (right) systemic JIA rash (Image courtesy of Barry L Myones, MD5)

Table 1. ILAR classification of JIA1

Blood tests are commonly conducted upon signs of JIA are observed. The levels of white blood cells and platelets would be increased with the occurrence of inflammation. In addition, inflammation may be reflected by elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), the levels of the biomarkers will be evaluated in the blood test as well. Furthermore, antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) status helps to classify certain subtypes of JIA.

In Enthesitis-Related Arthritis (ERA), the presence of HLA-B27 is associated with the onset of arthritis affecting joints in the lower limbs and the back in a boy after 6 years of age, whereas the identification of increased level of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies during blood test would be a risk factor of the disease6.

On the other hand, it is important to evaluate the skeletal condition of children with imaging study. X-ray can help to assess any soft tissue swelling and bone erosions. Diagnostic ultrasound can confirm the presence of synovitis, joint effusions and activities of the disease. Magnetic resonance imaging is useful to assess soft tissue involvement and to exclude other possibilities. Dr. Chong reminded that the presence of joint damage at diagnosis is a hint of severe disease and thus more aggressive treatment should be considered.

In response to the inquiry on the application of genetic testing in identifying risk factor of JIA, Dr. Chong commented that most JIA types are not resulting from a single gene mutation. Thus, genetic testing is not commonly considered in the diagnosis of JIA, unless for arthritis onset at very early stage of life.

Clinical Management of JIA

The overall goal of JIA treatment is to achieve remission, prevent joint damage and improve quality of life. In order to minimise long-term damage, the treatment should aim at early control of inflammation4.

First-line therapy for JIA is non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, in cases with established joint damage and/or non-responsive to NSAIDs, treatment with second-line therapy would be required. In prescribing second-line therapy, the specific subtype of JIA has to be taken into account. Methotrexate, sulfasalazine and leflunomide are examples of second-line therapy for JIA. Practically, second-line therapies may take some time to achieve the therapeutic effects. For patients with intolerance or suboptimal response to 2nd line treatment would need 3rd line therapy (e.g. biologics).

Nowadays, oral corticosteroids are less commonly used in managing JIA. Thanks to the pharmacological advancement, biologic therapies are available as 3rd line therapy for JIA. “Biologics are effective in controlling inflammation and prevent prolonged corticosteroid treatment,” commented Dr. Chong. He added that most of the treatments for JIA currently used are effective and safe while the conditions of patients have to be closely monitored.

Upon inflammation is under controlled, rehabilitation of muscle and joint mobility for daily functions is the next problem to be tackled. Thus, the involvement of a multidisciplinary team of professionals is required in the management of JIA. Physiotherapy and occupational therapy are essential for management of JIA patients. In severe cases, specialists in orthopaedics or other specialties would be involved. For JIA patients, regular examination by opthalmologists to exclude uveitis is required. As it is a kind of chronic illness, the emotion and social well-being of JIA patients and their family members have to be assessed. Counselling service by clinical psychologists in some of the cases may be considered. While long-term treatment of JIA would have financial impact on the family, it has to be taken into account during clinical management.

Impacts of JIA in Adulthood

The prognosis of JIA depends on multiple factors including the subtype of disease, age at onset, and the presence of autoantibodies. With the new generation of biologic therapies, most of the JIA cases can be well-controlled. Nonetheless, non-compliance to medicines during long-term management of JIA would contribute to an increased risk of active disease. A small proportion of patients with JIA live with the disease in their adulthood.

Certain clinical issues have been reported in adults with JIA. For instance, chronic anterior uveitis can continue and may flare with changes in treatment, such as cessation of treatment prior to pregnancy. Packham and Hall (2002) reported that uveitis occurred frequently in the oligoarticular-onset and enthesitis-related subsets7. On the other hand, Thornton et al (2011) demonstrated that adult females with the history of JIA had significantly lower bone mineral density and hence increased risk of osteoporosis and bone fracture8. Besides, some adults with JIA may need orthopaedic opinion and synovectomy for refractory single-joint disease9. Thus, adults with JIA may have significant levels of disability, which often related to continuing active disease over prolonged periods.

Fortunately, Dr. Chong addressed that there are local societies supporting patients with arthritis on their needs.

Transitional Care Matters

The treatment for children with JIA may be different from that for adult patients. Clinically, there will be a transition stage during which the patients are transferred from child- to adult-centred care. There are variations in medical, psychosocial and educational/vocational needs between adolescents and adults. Dr. Chong claimed that non-compliance to treatment is one of the main clinical concerns during the transition stage. It has been reported that transfer without appropriate preparation or at a time that coincides with challenging circumstances, such as ill health, examinations or family problems, is associated with poor clinical attendance and worse clinical outcomes10. Thus, there is a clear need for good transition from paediatric to adult rheumatology care.

Transitional care from paediatric to adult rheumatology care for JIA patients ideally involves a planned and coordinated transfer to adult rheumatologists with multi-disciplinary support. In particular, Dr. Chong suggested that primary care doctors should be involved in the long-term care of JIA. “For patients with stable or inactive disease, primary care doctors, who are usually the patients’ first consulting person, can cooperate with rheumatologists in managing the patients including monitoring patient’s conditions, assessing compliance and timely referral,” he addressed.

To optimise long-term health outcomes, paediatricians and rheumatologists handling JIA need to be aware of the wide range of patient issues, including transitional care, study and employment, sexual health and pregnancy as well as potential long-term co-morbidities, including bone health and cardiovascular diseases. Also, proper counselling for patients is required to address potential uncertainties about treatment options and long-term safety.

Early Diagnosis and Prompt Treatment - The Key for Preventing Long-term Impacts

Decades ago, the diagnosis of JIA relegated children to a lifetime of pain and disabilities, with increased risk of mortality. Nowadays, with the emergence of effective therapies, children with JIA are allowed to experience normal growth and activities. While oral targeted therapies for adults with arthritis are currently available, biologic therapies for JIA still involve injection which might discourage children compliance. Hence, Dr. Chong expressed that future works on development of oral targeted therapy for JIA are highly desirable.

Dr. Chong concluded that early diagnosis and subsequent appropriate treatment would undoubtedly help improve outcomes and prevent long-term impacts of JIA. Essentially, the involvement of a multidisciplinary team of professionals would ensure the seamless transition from paediatric to adult rheumatology care for the patients, hence enhancing their compliance to treatment and achieving optimal quality of life.

References

1. Petty et al, 2001. J Rheumatol 2004; 31: 390-2. 2. Saad. Open Orthop J 2020; 14: 101-9. 3. Palman et al. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2018; 32: 206-22. 4. Lee et al. HK J Paediatr 2003; 8: 21-30. 5. Sherry et al.Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Practice Essentials, Background, Etiology and Pathophysiology. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1007276-overview. 6. Hamooda et al. Electron Physician 2016; 8: 2897. 7. Packham and Hall. Rheumatology 2002; 41: 1428-35. 8. Thornton et al. J Rheumatol 2011; 38: 1689-93. 9. Iesaka et al. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2006; 35: 67-73. 10. Coulson et al. Rheumatology 2014; 53: 2155-66.